Frequently asked questions about

SB 9 development in California

California’s housing shortage has been decades in the making. SB 9, along with related state laws, is designed to unlock new opportunities for small-scale infill development in established neighborhoods. For developers and investors, these changes open up a pathway that avoids many of the delays and costs that have slowed traditional projects.

To help you navigate this evolving landscape, we’ve compiled answers to the most common questions about SB 9 — what it allows, why it matters, and what challenges remain.

Read through the FAQs below to understand the key issues shaping California’s housing future.

What is SB 9 and why is it important?

SB 9 stands for “Senate Bill 9” which was passed in California in late 2021. This bill was designed to allow property owners in California to build two primary units on one lot on underutilized land in residential neighborhoods, as well as the opportunity to split one lot into two. The net effect of SB 9 is to encourage development of more housing in California, to help address the housing affordability crisis there. When combined with Accessory Dwelling Unit (ADU) laws, SB 9 typically allows for up to four units to be built on a residential lot, rather than one home plus one guest house, which was allowed previously.

If SB 9 took effect in January 2022, why has it taken so long to start having any effect?

While the intent of SB 9 was to stimulate housing development, in its initial form, its impact was limited for a variety of reasons. The law contained unclear provisions that allowed opponents of development to slow down its implementation in the cities and counties that provide approval for new projects to go ahead. Furthermore, local politicians are very sensitive to the preferences of their local constituents, who tend to want to keep development out of their own neighborhoods. It wasn’t until several years later that further laws and clarification came through to allow developers to proceed with projects under these new laws. In light of litigation and these policy tweaks, there has been a learning curve for property owners and developers (as well as lenders) to adjust to the new SB 9 development pathway. This is similar to the multi-year ramp that has been seen with ADUs after laws were previously changed to make ADUs easier to develop.

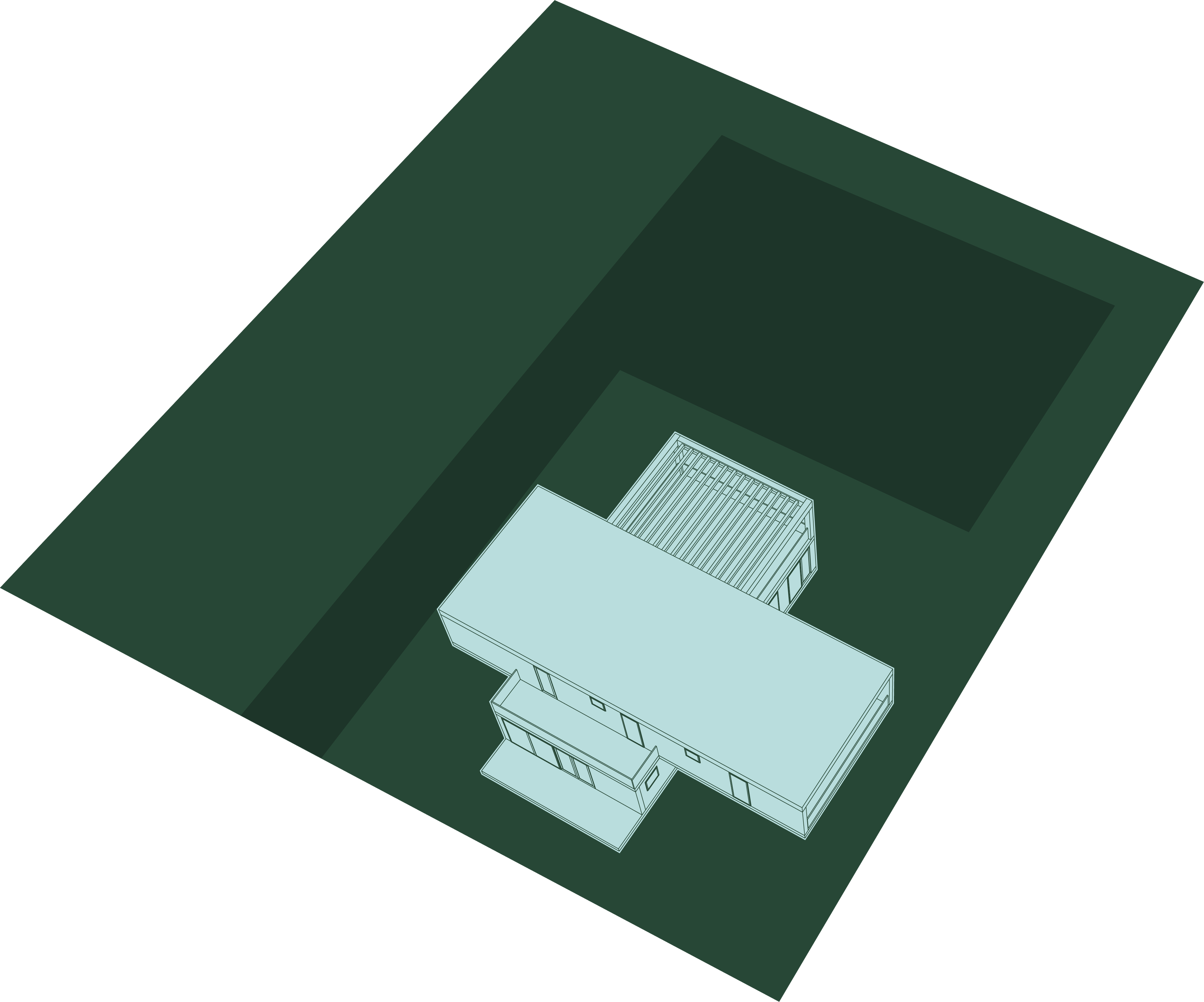

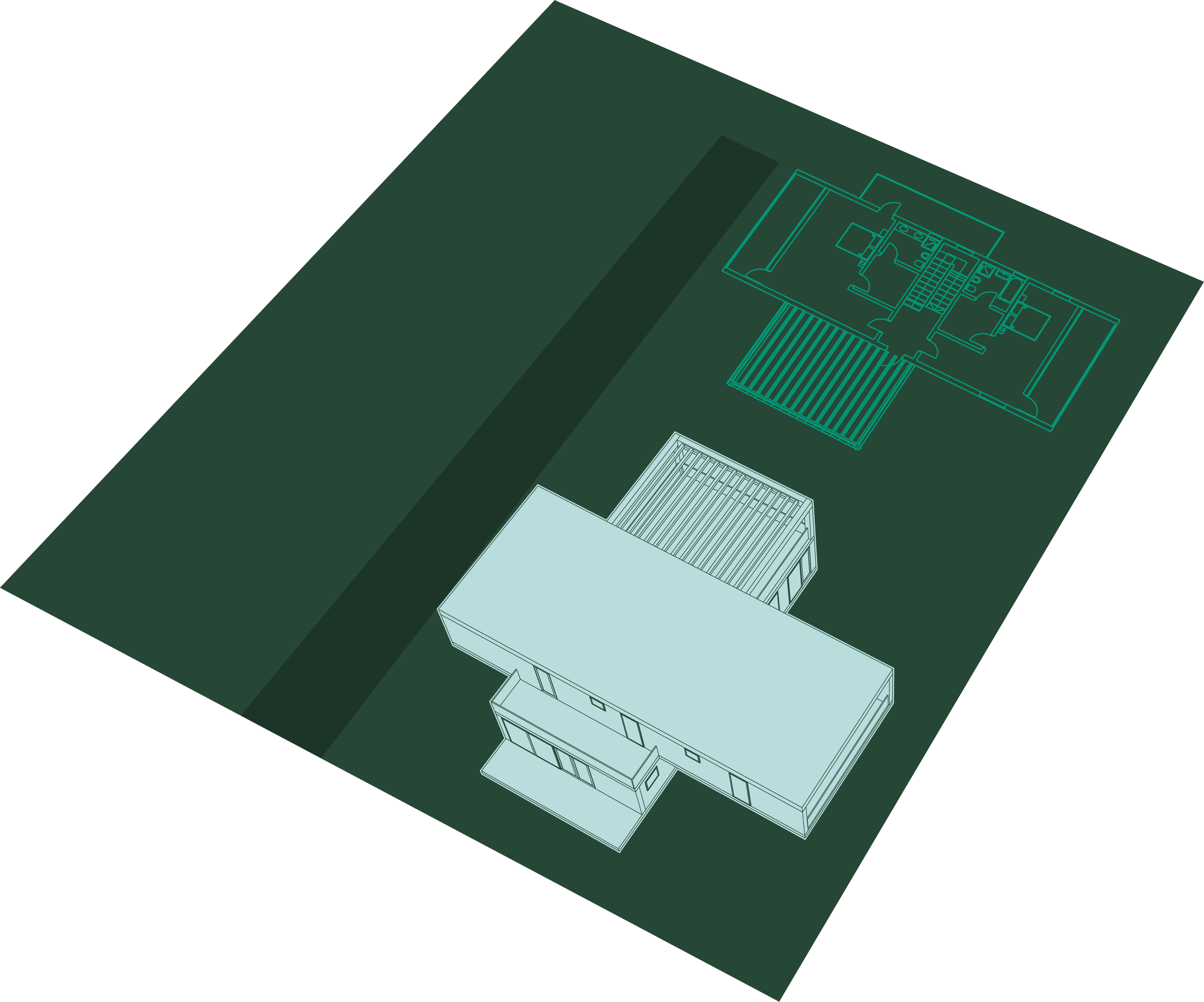

What are some of the central insights behind and advantages of SB 9?

SB 9 allows for more housing to be developed in existing, mature residential neighborhoods throughout California. These neighborhoods tend to be close to jobs, as opposed to new subdivisions that are frequently further away, requiring long commutes that degrade quality of life and contribute to global warming. SB 9 has also begun to unlock vacant land in the back yards of these mature neighborhoods that has traditionally not added much value to homes. Because developers can now build units on land that was underutilized, they are able to purchase buildable land in good locations, potentially at a fraction of the cost per lot that they would have previously paid for much less well located land on the outskirts of town. The result could be a renaissance of small-scale urban and suburban “infill” development projects throughout California. The term “infill” refers to development inside of established neighborhoods, in contrast to most new development in California which has traditionally been on the periphery of our cities. Additionally, infill development of small single-family homes, ADUs, and small lot splits tend to fit better into neighborhood character than large multi‑family buildings, while still expanding supply. This allows neighborhoods to maintain their character while increasing housing availability.

Why are SB 9 projects a bright spot for California real estate investment and development

Traditional real estate development is very slow, as of fall 2025, high interest rates and high construction costs have combined to bring down activity to historically very low levels. Furthermore, many investors are reluctant to commit capital to projects in California, because of the perception that policies could become more hostile to businesses and real estate investors over time, plus the very high cost of doing business there. SB 9 allows for ministerial approval (i.e., no discretionary hearings) which ideally enables developers to avoid many of the approval delays that often inhibit approvals for developers to execute on projects. For all of those reasons, SB 9-related development is one of the few bright spots on the horizon for real estate investing in the Golden State.

What are NIMBYs and why do they matter?

NIMBY stands for “not in my back yard”. It refers to the pattern of homeowners trying to block new construction and development in their own neighborhoods because they don’t want more traffic or any of the other byproducts of higher density. NIMBYs have been so successful for so long that by some counts, California has millions fewer residential units and homes compared to what is needed. This has contributed to rapidly escalating housing costs, which in turn led to a variety of problems such as longer commute times, high stress, and increased homelessness. Even though the urban areas of California have historically leaned heavily toward progressive values, homeowners have blocked efforts to take action that would ease the affordability crisis for those Californians that didn’t buy their homes when prices were much lower. Many Californians have agreed that we need to take action to ease the affordability crisis–just as long as it didn’t mean more development in their own neighborhoods!

What are YIMBYs and why do they matter?

YIMBY stands for “yes in my back yard”. This loose coalition has formed over time to counteract the powerful NIMBY movements in almost every city throughout California. YIMBYs recognized that in many cities, local politics is driven by homeowners who continue to block new development whenever they can. They devised a strategy to pass new laws at the state level, to override local opposition to new housing development.

Are some cities able to opt out of SB 9 and other pro-development state laws?

Generally, state law governs whenever there is a conflict between state and local laws. However, certain areas may be exempt from some pro-development laws, including areas with high fire hazards, historic districts, and flood zones. In addition, California has more than 100 “charter cities” which have more autonomy than typical cities, and these charter cities may be able to side-step the intent of the new state laws.

If this type of development takes off, what are the implications? Who benefits and who loses?

We believe that smaller developers will be the primary beneficiaries. There is no easy way to deploy large amounts of capital into SB 9-type projects, and so the largest developers and real estate equity investors will not be able to participate directly. At the same time, if free-standing rental units (and possibly for-sale ADU condominium units) are developed in urban infill “back yard” locations, this will create meaningful competition for traditional larger apartment building development and traditional subdivision-style home building. Many potential apartment dwellers might prefer to live in a free-standing building with a yard in a mature, quieter residential neighborhood, rather than a traditional apartment building, if the rent is similar. In other words, as small developers enjoy new opportunities, we expect that larger developers will need to gravitate away from California to focus on locations where large-scale projects are still competitive and cost-effective to build.

What is the potential scale across the state? And how does it compare to, for example, the LA fire zone rebuild?

UC Berkeley’s Terner Center for Real Estate has estimated that SB 9 could lead to as many as 700,000 new residential units being added across California. By comparison, the Los Angeles-area fires in early 2025 destroyed approximately 16,000 structures. If we assume a cost to rebuild of $2 million average in the fire zones, the total rebuilding cost would be approximately $32 billion. Meanwhile, if the cost per new unit for SB 9 construction is $500,000 average, the total construction cost of these ADU units would be $350 billion.

What are the major obstacles facing developers who plan to focus on this?

The biggest obstacle is that NIMBYs still have enormous influence in California politics. In every city, they are seeking ways to block the intended effects of higher density in their communities. At an even more local level, we expect lots of litigation from nearby homeowners trying to block specific projects, especially in the most affluent cities. It will be very interesting to see how this battle plays out, but for the first time ever, it appears that the YIMBYs have a plan to increase urban infill development substantially, in spite of local opposition.

What are related new laws and how might they ease the affordability crisis in both “for rent” and “for sale” housing?

In addition to SB 9, there is state law SB 684 and its update SB 1123 that may allow as many as 10 units to be built on residential vacant lots (those lots without an existing home). Assembly Bill (AB) 1033 allows ADUs to be sold individually as condominiums, and the City of San Jose is the first city to allow this and to have units actually on the market for sale. It’s important to note that AB 1033 requires cities to opt-in, as San Jose did.

To learn more visit our SB 9 Symposium recap page.

The information on this page is provided for general informational purposes only and reflects a summary of California’s pro-density housing laws, including SB 9. It may not include all requirements or local variations. These materials are not legal advice and should not be relied upon for making development, entitlement, or investment decisions. Readers should consult with a licensed attorney familiar with California land-use and real-estate law before acting on any information described here.